Researchers in the Coastal-Urban Resilience Laboratory investigate the physics of the coastal ocean and its interactions with the atmosphere and humans, applying a combination of computational modeling, statistical analysis and fixed observational stations. Our recent research converges toward an exciting new subfield of physical oceanography – the fluid dynamics of coastal risk and adaptation. Both natural and human systems will face relentless pressure in the coming decades from accelerating sea level rise and intensifying coastal storms, leading to rising opportunities for science-driven advancements towards improved coastal resilience, driven by academic research in physical oceanography.

Attribution of flooding to geomorphic and climatic change – Collaborative NSF funding I lead with a team across four institutions has enabled great progress in the study of interactions between coastal morphology change, sea level rise, tides and storm surge. Since the 19th century, estuary channels have typically been deepened and widened by a factor of two or three, harbor entrances have been deepened and streamlined, and a large proportion of wetlands have been filled over and replaced with neighborhoods. Such geomorphic changes, termed “estuary urbanization”, increase flood risk by reducing natural resistance to storm surge and tides.

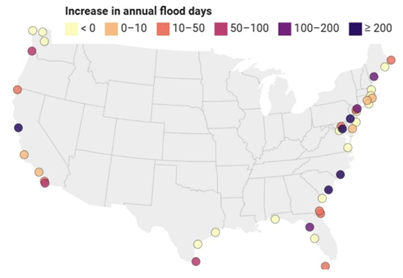

We used analysis of historical tide gauge observations to show how changing tides has led to large increases in the number of flood days since 1950 (top panel; Li et al., 2021; Orton & Talke, 2024). We also used a one-year hydrodynamic simulation of Jamaica Bay to demonstrate how landscape change can lead to a changed tidal probability distribution, rising flood frequency (lower panels; Pareja-Roman et al., 2023), and worsened storm tides (Orton et al., 2020). Similar findings apply to Miami’s chronic high-tide flooding (De Leo et al., 2022). Process-knowledge from this research is guiding the development of novel concepts for mitigation of coastal hazards such as shallowing inlets. We also performed the first attribution study for a coastal extreme storm surge, showing the anthropogenic climate-change driven sea level rise caused $8.1B in damages and 71000 additional people’s domiciles being flooded by Hurricane Sandy (Strauss et al., 2021).

Compound flooding – We recently studied compound flooding from three different approaches, led by a post-doc, doctoral student and now-graduated doctoral student, respectively: (1) joint probability assessment using historical data (Chen et al., submitted; Rosenzweig et al., 2024), (2) hydrodynamic model development to add pluvial (and thus, compound) flood capabilities to a coastal ocean model (Kasaei et al., 2024a), and (3) a comprehensive approach applying probabilistic assessment and hydrodynamic modeling to quantify flood hazard and adaptation benefits (Mita et al., submitted; Mita et al., 2023). Flood risk studies, insurance products and flood maps typically assume rain and storm surge are independent processes. Our analyses of historical data for the NYC metropolitan area showed that rain and storm surge generally have low, but non-zero correlations. However, tropical and post-tropical cyclones (TCs) have caused severe storm surges and extreme rainfall to occur simultaneously. Although assessment is limited by the small number of historical TC events, the limited evidence suggests that TCs can cause low probability, dangerous compound flooding (Chen et al., submitted; Rosenzweig et al., 2024). A collaboration with the US Geological Survey led to improvements to a widely-used coastal system model and creation of the first flood map for post-tropical cyclone Ida (2021) (Kasaei et al., 2024a; 2024b).

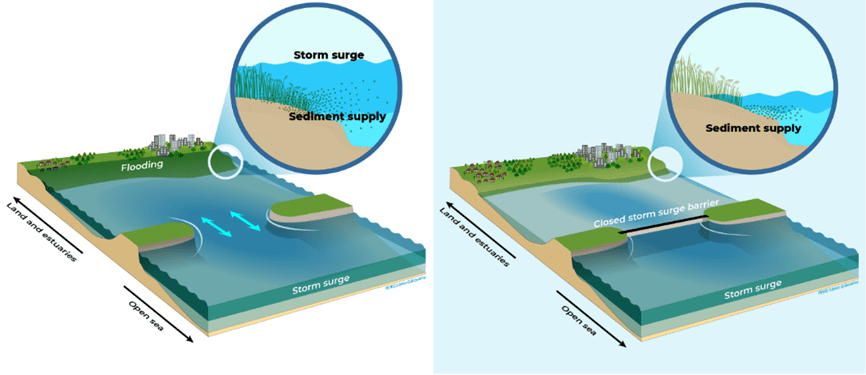

Storm surge barriers – opportunities to mitigate flooding, but dangers of maladaptation – Another research thread has been storm surge barriers, which we studied through a combination of dissertation research by Ziyu Chen and workshop-based consensus building among scientists, the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Hudson River National Estuary Research Reserve. Rising coastal flood risk and recent disasters are driving interest in the construction of gated storm surge barriers worldwide, with current studies recommending barriers for at least 11 estuaries in the United States alone. Surge barriers partially block estuary-ocean exchange with infrastructure across an estuary or its inlet and include gated areas that are closed only during flood events (see below).

Surge barriers can alter estuary stratification and salt intrusion (Chen & Orton, 2023), change sedimentary systems, and curtail animal migration and ecosystem connectivity, with impacts growing larger with increasing gate closures caused by sea level rise (Chen et al., 2020). The panel below contrasts the implications of a flood (left) with a closed off estuary protected by a storm surge barrier (Orton et al., 2023). Existing barriers are being used with increasing frequency due to sea level rise. New barrier proposals typically come with maximum closure frequency recommendations, yet the future adherence to them is uncertain. Given that the broader environmental effects and coupled-human dynamics of surge barriers are not well-understood, I led the development of an interdisciplinary research agenda for this increasingly prevalent modification to our coastal zone (Orton et al., 2023).

In prior years at Stevens, three primary research areas were (1) physics of coastal storm surge, (2) probabilistic assessment of coastal floods and climate change, and (3) mitigation or adaptation to coastal hazards, which saw vigorous interest regionally after the strong impacts of Hurricane Sandy.

In the topic area of physics of coastal storm surge, out contributions have shed light on its dependence on wind stress, wave radiation stress, coastal morphology, and estuary stratification and freshwater inputs. I contributed a major improvement to the Stevens Institute’s coastal flood forecasting system by incorporating the effects of storm waves on wind stress. That paper also demonstrated the importance of two estuary processes that are often neglected by other forecast systems, a widely-cited finding (Orton et al., 2012). Another area of great progress was the study of interactions between coastal morphology, tides and storm surge. Our published work revealed how inlet width and depth (Orton et al., 2015c), and tide resonance and sea level rise (Kemp et al., 2017; Orton et al., 2015b), all interact and influence coastal flooding. This new process knowledge, along with the model improvements described above, is guiding the development of novel concepts for mitigation of coastal hazards, discussed in the second and third topic areas below.

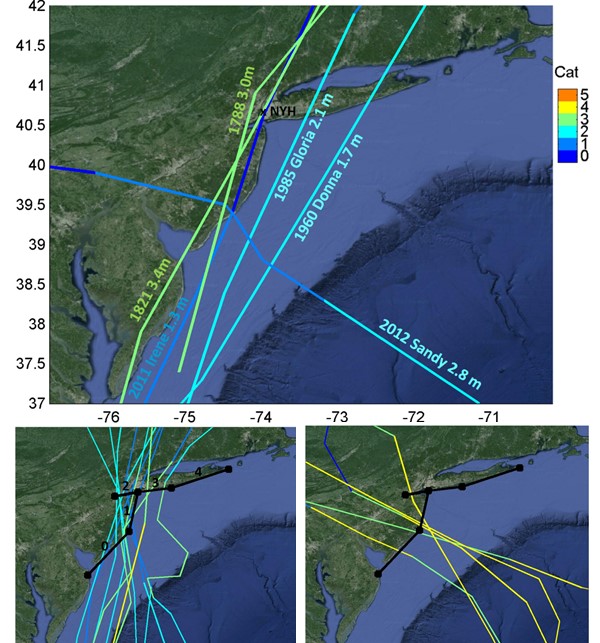

Probabilistic information on natural hazards is valuable for decision-makers, enabling mitigation studies and economic benefit-cost analyses that are often considered best-practices for development. However, hurricane flood probabilities form a particularly challenging problem, defined by rare events that may not have occurred in the brief historical record. In response to demand from New York City and other regional stakeholders, we developed novel dynamic modeling and probabilistic analysis techniques for quantifying flood risk from hurricanes at the coast (Orton et al., 2016b), as well as in tidal river systems where rainfall merges with storm surge (Orton et al., 2018). We have also extended these techniques to nonstationary analysis of evolving flood probabilities (Talke et al., 2014), included the effects of sea level rise (Orton et al., 2016a), and tested simplified flood mapping methods that alleviate the need for detailed dynamical modeling (Orton et al., 2015).

Studies of coastal hazard mitigation by engineered “gray” infrastructure and natural or nature-mimicking features are a natural follow-on to a disaster like Hurricane Sandy. The technical methods developed above have enabled much of my recent work in quantitative analysis of flood mitigation strategies. Immediately in the aftermath of Sandy, we were enlisted by New York City’s Special Initiative on Rebuilding and Resilience, leading to research showing that a small shift in Sandy’s landfall timing could have led to a worse flood disaster (Georgas et al., 2014). We contributed to New York City’s $20 billion flood mitigation plan (City of New York, 2013) and won the federal Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Rebuild By Design competition with a project called “Living Breakwaters” and generally studied how oysters or biochemically-attractive concrete can reduce coastal storm damages (Brandon et al., 2016; Orff et al., 2014). A broad range of quantitative analysis of flood mitigation efforts has followed, including benefit-cost analysis (Orton et al., 2016a) and physical modeling of water and waves moving through wetlands (Marsooli et al., 2016; Marsooli et al., 2017b). I proposed and modeled novel concepts for flood mitigation using sand replenishment in an estuary (Orton et al., 2016a; Orton et al., 2015c), and these results have subsequently received serious consideration in city-led community-guided mitigation studies.